Nan Madol City Of Spirits On The Reef Of Heaven

Nan Madol Cast like a net of gems over the not-so-Pacific Ocean, clusters of isles array its water vastness that drowns nearly a third of the Earth’s surface. Raised from hidden depths by volcanic force, these islands with their secluded shores, sun drenched and moon swept beaches, mangrove gardens, stone gods and temples grip the imagination.

One of the most renowned megalithic sites of these island worlds is Nan Madol, tagged the ‘Venice of the Pacific’ perched upon the southeastern coastline of Pohnpei. In landmass, Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) is the third-largest member of the Federated States of Micronesia, a spray of over 600 islands so-named after their minuscule size. Pohnpei is a compound name meaning “upon an altar”, in reference to a cloud-capped mountain in the island’s center: at its summit is an altar of basalt together with a mangrove tree which symbolically image the birth of the isle from its ocean bed.

Known traditionally as Soun Nan-leng or “the Reef of Heaven”, Nan Madol is a megalithic complex made up of over 90 man-made islets built on coral fill and spread200 acres [81 hectares] over a lagoon edging Pohnpei’s surrounding barrier reef.

The rectangular buildings of this lost metropolis, in such rare proximity to the natural systems of its environment, are assembled out of massive boulders and tidily stacked piles of prismatic basalt.The four-to eight-sided-columns of this dark, dense and smooth basalt material formed millions of year sago. When lava cools, it can have the distinctive appearance of hewn lumber so that sections of buildings made out of it resemble the crib work of log cabins.

Running around and in between the cryptic silence of the islets is a network of connecting waterways,while guarding Nan Madol from battering ocean tides are the ruins of breakwaters along its coast. The majority of crisscrossing waterways are today glutted with mangrove swamps,while thick tropical growth smothers nearly all of the islets - so making headway over either is a long, grueling task. If left unchecked,the invasion of jungle will devour the entire site and initiatives to restrain it are not forthcoming. To date,Nan Madol is not a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Today’s Pohnpeians , a modern people by global standards, are loath to visit the site and under no circumstances go there at night. They believe Nan Madol is haunted by ancient spirits and magic which should not be unsettled.

“Mystery” is often an overused term but is not without application here. Nan Madol exemplifies its definition: the site is unique the world over; it stands outside attested history, its people utterly vanished, its purpose spectacularly obscure. Construction of the site is currently perceived to date back no more than 1,500 years, although earlier foundations have been documented along with evidence of re modelling by successive occupants.

Modern scientific research of the complex began only in the 1960s and has largely been confined to topography and surface inspection - in the rare event it has been carried out at all.

Separated by a central canal, Nan Madol is divided into two main districts. Its southwestern area was allocated to what are believed to have been administrative and residential islets, while its northeastern islets housed its spiritual and mortuary temples and served as the focus of Nan Madol’s ritual activities.

The purpose of Nan Madol is not the only conundrum. Much remains obscure and unanswered about how such a colossal amount of basalt was quarried and transported to the site. Some of the stones have been chemically traced to a quarry on Pohnpei’s opposite end. How the hundreds of thousands of tons of material was brought here remains a boggling question. Was it ferried by raft along the coast or carted for miles over twisted terrain of mountain, hill, jungle, and swamp? A cornerstone of the mortuary islet of Nandauwas is estimated to weigh 60 tons, while the far smaller slabs and shafts commence from about five tons. The sheer quantity of material makes these transport routes and methods appear impossibly bleak. Constructed at a time when no more than 20,000 people inhabited the entire island, Nan Madol is an astounding feat, the Pohnpeian equivalent of the Giza pyramids.

Although named a “city”, Nan Madol even in its heyday would not correspond with how we identify one, or any other type of urban settlement. Though some of the buildings may have enjoyed pole-and-thatch roofing, the complex was not built with practical concerns in mind. With no access to fresh water, it was not for general living. Though picturesque, it was not a seaside getaway. Clearly ,Nan Madol was a priestly center with a defined spiritual agenda. The relatively shallow waterways, for example, which rise only waist deep even at high tide, were perhaps not intended solely to allow skiffs to travel between the islets but to enact rituals of initiation and journeys of the soul.

Although named a “city”, Nan Madol even in its heyday would not correspond with how we identify one, or any other type of urban settlement.

The name Nan Madol means “spaces between”, and its islets, arranged in a grid pattern, could therefore also be understood as houses harboring spirits from the spaces “in between” – another reason behind its unusual design and for the locals believing the place to be teeming with spirits. Indeed, deeply embedded in the creative genius and sacred vision of Nan Madol and its connection with water is the notion of a mirror image. As we shall see, it is a reflection of not only afterlife realms but also legacies of sunken cities beyond its shore. But who built this mysterious sub aquatic world that joins with others?

Argonauts of the Pacific

Today’s perspective on transoceanic migration between Pacific groups, Asia, and the Americas continues to transform at an alarming pace. The emerging picture holds Oceania to have been a much busier highway of exchange than was the view long before and after the days of Thor Heyerdahl’s ethnographic studies. A major barrier that prevented earlier consideration of nomadic outriggers’ contacting disparate cultures and ethnic groups was the question of seafaring. Basically, prehistoric peoples of Oceania were not ascribed navigational skills adequate enough to have crossed such vast sea distances and even relatively smaller ones between island chains, the trails of evidence left by these adventurous founders notwithstanding.

Though maritime structures and boats are not the most amenable to preservation, one cannot dismiss the forgotten methods of navigation enabling ancient seafarers to detect and colonies lands hidden within immense ocean wastes. These forgotten Sinbad s of the South navigated by signs such as species of bird that indicating nearby islands, types of fish associated with reefs and lagoons, cloud formations over distant landmasses, and sailing into swells bouncing back from land up to thousands of mile away. Sea bound for weeks to months through barrelling storms and the watery vastness, and guided by the compass and sextant of stars at night, these sailors performed hardcore feats of land-finding within gulfs of wilderness that have been compared with colonizing the frontiers of outer space in our time.

Pohnpei itself is said to have been settled over a wave of seven ancestor migrations that arrived on the island from the south. The seventh of these included two brother magicians named Olosopa and Olosipa to whom the construction of Nan Madol is accredited. Olosopa and Olosipa are said to have built the elaborate waterfront city with magic. The brothers arrived at Pohnpei in a canoe from a sinking homeland named Katau. Katau may or may not specify another Micronesian island named Kosrae, itself home to megalithic ruins, situated 345 miles [554 kilometers] southeast of Pohnpei. Since Katau is mentioned in reference to Pohnpei's earlier settlers, its geographical ambiguity perhaps indicates the degree to which locations on sea maps merged with mythical places in the sky seen above them.

The brothers Olosopa and Olosipa were related to a god of thunder and rain, and they brought to Pohnpei rituals and the worship of a god of agriculture under a dynasty known as the Saudeleur. Over generations their dynasty became tyrannical and was eventually overthrown by an outsider named Isokelekel, who was another exile from Katau.

When the brothers arrived at Pohnpei, they surveyed the island looking for a suitable location to settle their kingdom along the coast. They scaled a high mountain peak and from its vantage point saw an underwater city beyond the tidal flats southeast of the island.

They took this as a sign to build Nan Madol as the resurrection of the sunken “city” of Khanimweiso. There was yet a larger inspiration from sunken ruins behind the renaissance of Nan Madol, since it was said that there was another submerged city, this one named Namkhet, further out to sea beyond Khanimweiso.

For decades, divers have reported undersea ruins at considerable depth off the coast of Nan Madol. A diving team led by Dr. Arthur Saxe of Ohio State University in 1978 confirmed some of these sightings following a series of manual surveys in Nahkapw Harbor, which is overlooked by the breakwaters of Nandauwas. Saxe’s team reported a number of coral -encrusted stone pillars, some of them in an upright position. Saxe developed a hypothesis known as “Blue Hole” to explain how the structures sank. It involves a limestone cavern, which forms beneath reefs, imploding when its roof gives way. Saxe had it that Khanimweiso was built on top of a cavern that later collapsed. This would also account for the legends of tunnels below Nan Madol, some of them linked to different islets, since these caverns are characterized by interconnecting passages and “rooms”.

In 2013, Dr Saxe’s report was challenged by a Japanese marine archaeological survey. Following manual and multi beam sonar findings and informed by the research of a previous archaeological dive conducted by the University of Oregon in 1988-89, the team found one of the erect structures to be a natural formation rather than a coral encrusted pillar. The Japanese researchers also question Dr Saxe’s Blue Hole hypothesis as being unlikely, but concede that their findings do not rule it, or the possible existence of undersea heritage, out. Their survey was also confined to the harbor rather than outside it. Though we do not have access to these offshore ruins at present, the Nan Madol site was built as a reflection of something in that direction.

The basaltic rock from which Nan Madol is built was a material of esteemed spiritual standing not only to the ancient Pohnpeians but also to other island people far from the water margins of Nan Madol. The neighborly isles of Truk, Kosrae, Ngartik and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands were united by a basalt cult. Basalt shrines on mountain peaks were spirit places, and basalt monoliths the abodes of gods and ancestors. In addition to housing spirits, these “stone gods”, literally blocks of basalt, marked the place of origin of clans since they embodied their founders. This widespread diffusion is naturally believed to have originated from mountainous islands such as Kosrae and Pohnpei, where basalt was found and quarried and then imported to the lower lands and atolls of Ngartik and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands.

Significantly, basalt was also connected to a cosmic god of thunder and rain who was named Daukatau, meaning “Master of Katau”, with whom the brothers Olosopa and Olosipa had dealings. Daukatau is believed to be a protoOceanic title; it curiously does not affiliate well with Pacific etymologies, although Katau, the mythical homeland of the Pohnpeians, has been translated as “high place” or, likewise, “basalt peak”.

The character of Daukatau is not far below the surface in the diffusion of this cult. In the Gilbert Islands, a thunder deity named Tabuariki – a chunk of basalt – was worshiped. As basaltic rock was perceived as conducive to channeling supernatural powers and for domesticating the thunder god Daukatau, it is relevant that Nan Madol is built from basalt: it explains, a little, the extraordinary measures behind the quarrying and transport of this heavy mineral.

Belief in the magical properties of basalt was not confined to these shores; the material found home at other places far distanced from these islands.

In the Cianjur Regency of Java, the site named Gunung Padang – “the mountain of light/seeing” - recently emerged from archival level obscurity. Built out of basalt, it is assembled upon a dormant volcano that rises sharply 2,900 feet [884 meters] above sea level. The outer layers of this pyramid or platform structure are stacked with columnar basalt joints. The five mounting terraces at its summit are lightly picketed by the same columns. Unlike at Nan Madol, the columns at Gunung Padang are staked in the ground quite randomly and appear like eldritch tombstones. Significantly, the basalt columns were similarly connected to a thunder god who took the form of a dragon and was believed to have influence over baleful meteorological phenomena accordingly.

The remoter Easter Island also had a strong tradition with this igneous material from which the Moai statues were produced. It was named Ma’ea Matariki, Ma’ea meaning stone and Matariki meaning “to reference both the ancestors and that star cluster [i.e., the Pleiades]”. As “living images” or mediums of this energy, the statues were said to come alive twice a year when the dead would visit the living.

The construction of Nan Madol and Gunung Padang and the Moai of Easter Island are wrapped in analogous auras of mystery. Nan Madol was built by a magic known as Manaman, while the Moai were said to have been levitated by a force known as Mana. Gunung Padang is said to have been built para normally in only one night.

Covering an area the size of a football pitch, Nandauwas was allegedly a mortuary complex that housed the royal tombs of the Saudeleur, although no confirmed archaeological remains of this type have ever been found there. Set back from the water immersed perimeter base of Nandauwas, towering piles of lava slabs form a surrounding wall up to 25 feet [7.6 meters] high, its corners finished in up swept peaks as if to mimic a boat or sea-going vessel. As on Easter Island, spirit ships or soul boats were sacred items connected with ancestor worship, commemorating how the forefathers had arrived to these shores from their sinking homelands. They also enabled travel over spirit paths to the realm of the afterlife on the horizon. On some islands, setting an embalmed body adrift in a boat-shaped coffin was practiced. Similar to ancient Egyptian “barges of the dead”, boat tombs and burials have been found over the Pacific. Thus, a spirit ship may have been an eminent concept behind the design of Nandauwas.

Behind its elegantly sweeping western portal are rectangular courts enclosing a central subterranean tomb vaulted by hefty five-ton basalt girders. Beneath an emerald glaze of jungle are other crypts, tunnels and courtyards and a ledge coursing along the interior of the outer walls, its purpose unspecified. Sited behind the ruins of its massive breakwater that reaches out to the harbors edge like giant arms, Nandauwas is built on an east-west axis and is offset more to the east from the rest of Nan Madol. Nandauwas was a ritual space, not an observatory. Its portions are not constantly recurring, but there is a reason for its irregular orientation.

The star cluster most regarded by the ancient Pohnpeians was the Pleiades. In fact, the attention given to this relatively unassuming cluster is quite astounding given the unobscured, unpolluted vistas of the sky at night.

The eastern wall of Nandauwas looks seaward over the harbor in a direction that not only targets Nan Madol’s legendary Khanimweiso and Namkhet sunken archetypes but also the vanished motherland of Katau, whether Katau be identified with Kosrae or not.

Celestial phenomena enters this equation. Both the equinoxes and the June solstice are visible from the east-facing seaward wall of Nandauwas. Perhaps more significant, marked between these solar stations at the time of Nan Madol's construction and use was the rising of the Pleiades.

These stars were not only revered for predicting a heavy harvest and for allowing plotting of the ritual calendar, but from the seaward wall of Nandauwas they would suggestively appear to rise from the realm of the dead and sunken homeland on the southeastern horizon, providing a reason for why Nandauwas, offset from the rest of Nan Madol, would interlock with them.

Indeed, one is also inclined to think of the seven founding ancestor voyages responsible for settling Pohnpei, which arrived on the island from this direction, as reinforcing the Pleiades connection further. As with the Moai of Easter Island, did the ancestors revisit and possess Nandauwas on certain eves?

As with Easter Island, the Pleiades connect implicitly with traditions of sunken legacies. We are reminded that before the dramatic rise in sea levels following the last major glacial meltdown, Pohnpei was an unrecognizable larger volcanic landmass than it currently is. For an island unblemished by marauding contact for millennia, might not Olosopa and Olosipa's account of an underwater city off the coast preserve the imprint of a distant cultural memory, for which Nan Madol was built as the resurrection?

By Alistair Coombs

References

Ballinger, Bill S., Lost City of Stone: The Story of Nan Madol, the “Atlantis” of the Pacific, Simon Esteban, César, “Some Notes on Orientations of Prehistoric Stone Monuments in Western Polynesia Goodenough, Ward H., “Sky World and This World: The Place of Kachaw in Micronesian Ishimura, Tomo et al., “Underwater Survey at the Ruins of Nan Madol, Pohnpei State, Federated Malone, Mike, “Micronesia’s Star-Path Navigators”, Glimpses of Micronesia (Agana, Guam) 1983; Morgan, William N., Prehistoric Architecture in Micronesia, Kegan Paul, London, 1989 & Schuster, New York, 1979and Micronesia”, Archaeoastronomy: The Journal of Astronomy in Culture, 2003; XVIICosmology”, American Anthropologist 1986; 88(3): 551-568 States of Micronesia”, 2013 23(4) Saxe Arthur et al, “The Nan Madol Area of Ponape: Researches into Bounding and Stabilizing an Ancient Administrative Center”, Trust Territory of the Pacific, Saipan, Mariana Islands, 1980.

The brothers Olosopa and Olosipa were related to a god of thunder and rain, and they brought to Pohnpei rituals and the worship of a god of agriculture under a dynasty known as the Saudeleur. Over generations their dynasty became tyrannical and was eventually overthrown by an outsider named Isokelekel, who was another exile from Katau.

When the brothers arrived at Pohnpei, they surveyed the island looking for a suitable location to settle their kingdom along the coast. They scaled a high mountain peak and from its vantage point saw an underwater city beyond the tidal flats southeast of the island.

They took this as a sign to build Nan Madol as the resurrection of the sunken “city” of Khanimweiso. There was yet a larger inspiration from sunken ruins behind the renaissance of Nan Madol, since it was said that there was another submerged city, this one named Namkhet, further out to sea beyond Khanimweiso.

For decades, divers have reported undersea ruins at considerable depth off the coast of Nan Madol. A diving team led by Dr. Arthur Saxe of Ohio State University in 1978 confirmed some of these sightings following a series of manual surveys in Nahkapw Harbor, which is overlooked by the breakwaters of Nandauwas. Saxe’s team reported a number of coral -encrusted stone pillars, some of them in an upright position. Saxe developed a hypothesis known as “Blue Hole” to explain how the structures sank. It involves a limestone cavern, which forms beneath reefs, imploding when its roof gives way. Saxe had it that Khanimweiso was built on top of a cavern that later collapsed. This would also account for the legends of tunnels below Nan Madol, some of them linked to different islets, since these caverns are characterized by interconnecting passages and “rooms”.

In 2013, Dr Saxe’s report was challenged by a Japanese marine archaeological survey. Following manual and multi beam sonar findings and informed by the research of a previous archaeological dive conducted by the University of Oregon in 1988-89, the team found one of the erect structures to be a natural formation rather than a coral encrusted pillar. The Japanese researchers also question Dr Saxe’s Blue Hole hypothesis as being unlikely, but concede that their findings do not rule it, or the possible existence of undersea heritage, out. Their survey was also confined to the harbor rather than outside it. Though we do not have access to these offshore ruins at present, the Nan Madol site was built as a reflection of something in that direction.

Gods of Thunder

To the ancient island dwellers, the ocean represented the pervasive fabric of the cosmos. It bounded all horizons. From an island-centered perspective, the limits of sight and awareness where sea and sky met and melted in sunlit azure or faded in waves of galactic expanse at night signposted the land of the dead. The ancestor world on the horizon could also refer to impenetrable marine trenches far from land, where objects might rise to the surface. Things that came to shore from the beyond, such as driftwood or anomalous marine life, were possessed with portent and power - a view reinforced by tradition that ancestral founders of dynastic lines had come from outside.The basaltic rock from which Nan Madol is built was a material of esteemed spiritual standing not only to the ancient Pohnpeians but also to other island people far from the water margins of Nan Madol. The neighborly isles of Truk, Kosrae, Ngartik and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands were united by a basalt cult. Basalt shrines on mountain peaks were spirit places, and basalt monoliths the abodes of gods and ancestors. In addition to housing spirits, these “stone gods”, literally blocks of basalt, marked the place of origin of clans since they embodied their founders. This widespread diffusion is naturally believed to have originated from mountainous islands such as Kosrae and Pohnpei, where basalt was found and quarried and then imported to the lower lands and atolls of Ngartik and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands.

Significantly, basalt was also connected to a cosmic god of thunder and rain who was named Daukatau, meaning “Master of Katau”, with whom the brothers Olosopa and Olosipa had dealings. Daukatau is believed to be a protoOceanic title; it curiously does not affiliate well with Pacific etymologies, although Katau, the mythical homeland of the Pohnpeians, has been translated as “high place” or, likewise, “basalt peak”.

The character of Daukatau is not far below the surface in the diffusion of this cult. In the Gilbert Islands, a thunder deity named Tabuariki – a chunk of basalt – was worshiped. As basaltic rock was perceived as conducive to channeling supernatural powers and for domesticating the thunder god Daukatau, it is relevant that Nan Madol is built from basalt: it explains, a little, the extraordinary measures behind the quarrying and transport of this heavy mineral.

Belief in the magical properties of basalt was not confined to these shores; the material found home at other places far distanced from these islands.

In the Cianjur Regency of Java, the site named Gunung Padang – “the mountain of light/seeing” - recently emerged from archival level obscurity. Built out of basalt, it is assembled upon a dormant volcano that rises sharply 2,900 feet [884 meters] above sea level. The outer layers of this pyramid or platform structure are stacked with columnar basalt joints. The five mounting terraces at its summit are lightly picketed by the same columns. Unlike at Nan Madol, the columns at Gunung Padang are staked in the ground quite randomly and appear like eldritch tombstones. Significantly, the basalt columns were similarly connected to a thunder god who took the form of a dragon and was believed to have influence over baleful meteorological phenomena accordingly.

The remoter Easter Island also had a strong tradition with this igneous material from which the Moai statues were produced. It was named Ma’ea Matariki, Ma’ea meaning stone and Matariki meaning “to reference both the ancestors and that star cluster [i.e., the Pleiades]”. As “living images” or mediums of this energy, the statues were said to come alive twice a year when the dead would visit the living.

The construction of Nan Madol and Gunung Padang and the Moai of Easter Island are wrapped in analogous auras of mystery. Nan Madol was built by a magic known as Manaman, while the Moai were said to have been levitated by a force known as Mana. Gunung Padang is said to have been built para normally in only one night.

Nandauwas: Gateway of the Dead

Rising steeply from the grid of silent waterways in the northeastern quarter of Nan Madol, towering stacks of boulders and columns bulwark the inner sanctuary of Nandauwas – the jewel in the crown of Nan Madol and the largest megalithic structure of Micronesia. Nandauwas is majestic yet austere, enigmatic and elusively forbidding. Along its blackened seaward-facing stretch it can appear vaguely ominous, an impression cast by its precipitous rise and unfamiliar outline which recalls the fear the locals have of the place.Covering an area the size of a football pitch, Nandauwas was allegedly a mortuary complex that housed the royal tombs of the Saudeleur, although no confirmed archaeological remains of this type have ever been found there. Set back from the water immersed perimeter base of Nandauwas, towering piles of lava slabs form a surrounding wall up to 25 feet [7.6 meters] high, its corners finished in up swept peaks as if to mimic a boat or sea-going vessel. As on Easter Island, spirit ships or soul boats were sacred items connected with ancestor worship, commemorating how the forefathers had arrived to these shores from their sinking homelands. They also enabled travel over spirit paths to the realm of the afterlife on the horizon. On some islands, setting an embalmed body adrift in a boat-shaped coffin was practiced. Similar to ancient Egyptian “barges of the dead”, boat tombs and burials have been found over the Pacific. Thus, a spirit ship may have been an eminent concept behind the design of Nandauwas.

Behind its elegantly sweeping western portal are rectangular courts enclosing a central subterranean tomb vaulted by hefty five-ton basalt girders. Beneath an emerald glaze of jungle are other crypts, tunnels and courtyards and a ledge coursing along the interior of the outer walls, its purpose unspecified. Sited behind the ruins of its massive breakwater that reaches out to the harbors edge like giant arms, Nandauwas is built on an east-west axis and is offset more to the east from the rest of Nan Madol. Nandauwas was a ritual space, not an observatory. Its portions are not constantly recurring, but there is a reason for its irregular orientation.

The star cluster most regarded by the ancient Pohnpeians was the Pleiades. In fact, the attention given to this relatively unassuming cluster is quite astounding given the unobscured, unpolluted vistas of the sky at night.

The eastern wall of Nandauwas looks seaward over the harbor in a direction that not only targets Nan Madol’s legendary Khanimweiso and Namkhet sunken archetypes but also the vanished motherland of Katau, whether Katau be identified with Kosrae or not.

Celestial phenomena enters this equation. Both the equinoxes and the June solstice are visible from the east-facing seaward wall of Nandauwas. Perhaps more significant, marked between these solar stations at the time of Nan Madol's construction and use was the rising of the Pleiades.

These stars were not only revered for predicting a heavy harvest and for allowing plotting of the ritual calendar, but from the seaward wall of Nandauwas they would suggestively appear to rise from the realm of the dead and sunken homeland on the southeastern horizon, providing a reason for why Nandauwas, offset from the rest of Nan Madol, would interlock with them.

Indeed, one is also inclined to think of the seven founding ancestor voyages responsible for settling Pohnpei, which arrived on the island from this direction, as reinforcing the Pleiades connection further. As with the Moai of Easter Island, did the ancestors revisit and possess Nandauwas on certain eves?

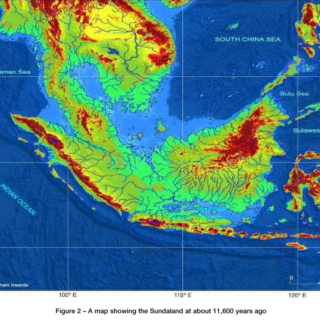

As with Easter Island, the Pleiades connect implicitly with traditions of sunken legacies. We are reminded that before the dramatic rise in sea levels following the last major glacial meltdown, Pohnpei was an unrecognizable larger volcanic landmass than it currently is. For an island unblemished by marauding contact for millennia, might not Olosopa and Olosipa's account of an underwater city off the coast preserve the imprint of a distant cultural memory, for which Nan Madol was built as the resurrection?

By Alistair Coombs

References

Ballinger, Bill S., Lost City of Stone: The Story of Nan Madol, the “Atlantis” of the Pacific, Simon Esteban, César, “Some Notes on Orientations of Prehistoric Stone Monuments in Western Polynesia Goodenough, Ward H., “Sky World and This World: The Place of Kachaw in Micronesian Ishimura, Tomo et al., “Underwater Survey at the Ruins of Nan Madol, Pohnpei State, Federated Malone, Mike, “Micronesia’s Star-Path Navigators”, Glimpses of Micronesia (Agana, Guam) 1983; Morgan, William N., Prehistoric Architecture in Micronesia, Kegan Paul, London, 1989 & Schuster, New York, 1979and Micronesia”, Archaeoastronomy: The Journal of Astronomy in Culture, 2003; XVIICosmology”, American Anthropologist 1986; 88(3): 551-568 States of Micronesia”, 2013 23(4) Saxe Arthur et al, “The Nan Madol Area of Ponape: Researches into Bounding and Stabilizing an Ancient Administrative Center”, Trust Territory of the Pacific, Saipan, Mariana Islands, 1980.

This article was published in the June 2016 issues of Ancient Mysteries International. It is Printed here with Permission. Permission is granted to quote brief passages by journalists and reviewers. It is printed here in cooperation with Ancient Mysteries International.

If you enjoyed my site or this article please consider making a donation your help is much appreciated.

Comments

Post a Comment